Lick's Historical Collections: Background

Early view of Lick Observatory.

Lick Observatory arrived on the scene at the beginning of a new era in astronomy.

The great advances in chemistry and physics of the nineteenth century were opening new avenues

of investigation, and the application of laboratory methods and new technologies at the telescope

was revolutionizing observing. Classical astronomy—the observation of positions and

motions—was reinventing itself as the modern science of astrophysics.

Astronomy is a technology-driven science. Advances in instrumentation that increase the power

and precision of observations almost always lead to discoveries. Lick's early success with

the "new astronomy" and its 120 years of continued prominence in a rapidly changing astronomical

landscape have been due in large measure to its aggressive development of innovative instruments

and observing techniques.

Early view of Lick Observatory.

Lick Observatory arrived on the scene at the beginning of a new era in astronomy.

The great advances in chemistry and physics of the nineteenth century were opening new avenues

of investigation, and the application of laboratory methods and new technologies at the telescope

was revolutionizing observing. Classical astronomy—the observation of positions and

motions—was reinventing itself as the modern science of astrophysics.

Astronomy is a technology-driven science. Advances in instrumentation that increase the power

and precision of observations almost always lead to discoveries. Lick's early success with

the "new astronomy" and its 120 years of continued prominence in a rapidly changing astronomical

landscape have been due in large measure to its aggressive development of innovative instruments

and observing techniques.

Items in the scientific objects collection.

Over the decades Lick has helped to pioneer technologies such as astrophotography, spectroscopy,

photoelectric photometry, electronic imaging, advanced optics, telescope control, and digital

astronomy. The technological turnover resulting from the constant introduction of new, more

capable instruments and the retirement of older ones is a century-old pattern at Lick that has

left a trove of historically interesting scientific objects in its wake.

Observational astronomy has advanced so rapidly since Lick's founding that objects can quickly

acquire historical importance. Our collection is extraordinary for spanning more

than a hundred years and including examples from every era

of the observatory's history and every species of observing. The collection is a fossil record of

the evolution of observational astronomy since the observatory's founding.

Lick's scientific stature and its long tradition of instrument development lend exceptional

interest to its collection of scientific objects. Many have significance in the history of

technology, are associated with outstanding astronomers and important observing programs, or

have notable provenances. They are valuable teaching tools and first-source materials for the

history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century science. Most are unique, and many are

elegant—even beautiful—in their own right.

Items in the scientific objects collection.

Over the decades Lick has helped to pioneer technologies such as astrophotography, spectroscopy,

photoelectric photometry, electronic imaging, advanced optics, telescope control, and digital

astronomy. The technological turnover resulting from the constant introduction of new, more

capable instruments and the retirement of older ones is a century-old pattern at Lick that has

left a trove of historically interesting scientific objects in its wake.

Observational astronomy has advanced so rapidly since Lick's founding that objects can quickly

acquire historical importance. Our collection is extraordinary for spanning more

than a hundred years and including examples from every era

of the observatory's history and every species of observing. The collection is a fossil record of

the evolution of observational astronomy since the observatory's founding.

Lick's scientific stature and its long tradition of instrument development lend exceptional

interest to its collection of scientific objects. Many have significance in the history of

technology, are associated with outstanding astronomers and important observing programs, or

have notable provenances. They are valuable teaching tools and first-source materials for the

history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century science. Most are unique, and many are

elegant—even beautiful—in their own right.

The Historical Collections Project: Cataloging the Scientific Objects

Until recently, the significance of the scientific objects as a coherent historical collection

was not widely recognized. The objects were largely unrecorded and haphazardly stored

in various places on Mt. Hamilton, putting them at risk from mishandling, misplacement, casual

lending, cannibalism for parts, and accidental or misguided disposal.

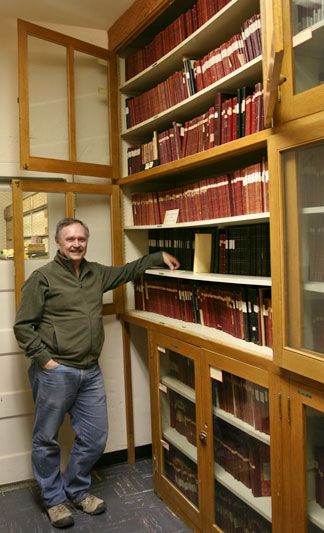

Cabinets in the scientific objects archive.

Cabinets in the scientific objects archive.

Shelves in the scientific objects archive.

In November 2008 the observatory, recognizing the value and special vulnerability of the

scientific objects, began the Historical Collections Project for

their protection. The aims of this project are to locate and catalog the important scientific

objects and to provide a safe and secure location for them, and to make information about the

collection available to the public for education and historical research.

Systematic cataloging is a necessary first step to achieving the aims of protecting the objects

and transforming them into an organized, accessible collection. We therefore began by designing

and implementing an electronic database specially tailored to the requirements of cataloging the

scientific objects, but with the built-in flexibility to accommodate all or parts of the two

related collections.

Shelves in the scientific objects archive.

In November 2008 the observatory, recognizing the value and special vulnerability of the

scientific objects, began the Historical Collections Project for

their protection. The aims of this project are to locate and catalog the important scientific

objects and to provide a safe and secure location for them, and to make information about the

collection available to the public for education and historical research.

Systematic cataloging is a necessary first step to achieving the aims of protecting the objects

and transforming them into an organized, accessible collection. We therefore began by designing

and implementing an electronic database specially tailored to the requirements of cataloging the

scientific objects, but with the built-in flexibility to accommodate all or parts of the two

related collections.

Photographing the scientific objects.

Cataloging an object begins with the assignment of a unique identifier. We then digitally

photograph the object, making as many images as are needed to illustrate it completely. After

processing, the images become part of the object's database record, along with a physical

description and—where known—notes on its function, application, history, association,

and provenance. In some cases published or handwritten references exist that enrich an object's

description. Where such references are available in digital form, the object's record includes a

link to them.

Once entered in the database, an object and its full description become available on our website

where visitors can browse the database or search it by categories and keywords. The website and

online database are aimed at a diverse audience: scholars, educators, students, artists, and

anyone else interested in the history of science and technology.

Photographing the scientific objects.

Cataloging an object begins with the assignment of a unique identifier. We then digitally

photograph the object, making as many images as are needed to illustrate it completely. After

processing, the images become part of the object's database record, along with a physical

description and—where known—notes on its function, application, history, association,

and provenance. In some cases published or handwritten references exist that enrich an object's

description. Where such references are available in digital form, the object's record includes a

link to them.

Once entered in the database, an object and its full description become available on our website

where visitors can browse the database or search it by categories and keywords. The website and

online database are aimed at a diverse audience: scholars, educators, students, artists, and

anyone else interested in the history of science and technology.

Some late nineteenth century lenses in the scientific objects collection.

Until the current cataloging effort, the only record of objects was an "accession" file,

containing cards with brief descriptions of about 750 objects (the most recent entries appear to

be from the mid-1930's). Of the objects recorded in the accessions file, fewer than half have been

identified in the current collection; the remainder are missing and presumed lost. (The file,

however, is not exhaustive; many items present in the collection—though acquired before the

1930's—are not recorded in the file.) A few objects have University of California inventory

numbers, but from an apparently superannuated numbering system, and we have been unable thus far

to find inventory records that would help identify them.

In the absence of an accession card or other clue to an object's identity, its database entry still

contains, at the very least, photographs and a physical description. In many cases, even though an

object's particular history and application are unknown, its purpose or function is clear. Clues,

such as a maker's name or an object's similarity to an identified item in the collection, can

lead to more specific identification. Even where an accession card exists for an object, writing a

complete and accurate description can be challenging, as the cards often provide only vague or

minimal information. (Scans of accession cards are included in the database records of objects that

have one.)

Some late nineteenth century lenses in the scientific objects collection.

Until the current cataloging effort, the only record of objects was an "accession" file,

containing cards with brief descriptions of about 750 objects (the most recent entries appear to

be from the mid-1930's). Of the objects recorded in the accessions file, fewer than half have been

identified in the current collection; the remainder are missing and presumed lost. (The file,

however, is not exhaustive; many items present in the collection—though acquired before the

1930's—are not recorded in the file.) A few objects have University of California inventory

numbers, but from an apparently superannuated numbering system, and we have been unable thus far

to find inventory records that would help identify them.

In the absence of an accession card or other clue to an object's identity, its database entry still

contains, at the very least, photographs and a physical description. In many cases, even though an

object's particular history and application are unknown, its purpose or function is clear. Clues,

such as a maker's name or an object's similarity to an identified item in the collection, can

lead to more specific identification. Even where an accession card exists for an object, writing a

complete and accurate description can be challenging, as the cards often provide only vague or

minimal information. (Scans of accession cards are included in the database records of objects that

have one.)

Objective for one of the five-foot Einstein-effect cameras (1922).

Much cataloging remains, but the effort so far has already been rewarded with a number of

significant finds. For example, early in the project we identified three of the four lenses of the

15-foot Einstein-effect camera, used at the 1922 solar eclipse to verify the Theory of General

Relativity. Soon after, we found two additional parts of the camera stored in another part of the

observatory, enabling us to reunite the lenses in their original optical arrangement. The

understanding of the instrument thus gained led us more recently to identify another pair of

complex lens assemblies belonging to the 5-foot Einstein-effect camera used at the same eclipse.

Another example of serendipitous discoveries resulting from systematic cataloging has been the

identification of scattered parts of two of Lick's most significant instruments of the late

nineteenth century: (a) the Keeler Star Spectroscope, with which James Keeler set the

"high water mark" for visual radial velocity studies, and (b) the Crocker Telescope used by

E. E. Barnard for his epoch-making photographs of the Milky Way and comets. These finds will,

we hope, make it possible to one day restore these famous instruments.

Objective for one of the five-foot Einstein-effect cameras (1922).

Much cataloging remains, but the effort so far has already been rewarded with a number of

significant finds. For example, early in the project we identified three of the four lenses of the

15-foot Einstein-effect camera, used at the 1922 solar eclipse to verify the Theory of General

Relativity. Soon after, we found two additional parts of the camera stored in another part of the

observatory, enabling us to reunite the lenses in their original optical arrangement. The

understanding of the instrument thus gained led us more recently to identify another pair of

complex lens assemblies belonging to the 5-foot Einstein-effect camera used at the same eclipse.

Another example of serendipitous discoveries resulting from systematic cataloging has been the

identification of scattered parts of two of Lick's most significant instruments of the late

nineteenth century: (a) the Keeler Star Spectroscope, with which James Keeler set the

"high water mark" for visual radial velocity studies, and (b) the Crocker Telescope used by

E. E. Barnard for his epoch-making photographs of the Milky Way and comets. These finds will,

we hope, make it possible to one day restore these famous instruments.

The Coblentz thermopile (ca. 1912).

Other important finds include several in the area of early electronic instrumentation. One, the

Coblentz thermopile—a delicate glass device dating from about 1912—was the first detector used to make

accurate measurements of infrared starlight. Another, an elegant string electrometer, was used with

Lick's first photoelectric photometer, built in 1923 by graduate student Elizabeth Cummings. A

third is the Kron-Whitford photometer from about 1930—the first of its type to use an evacuated

chamber to reduce detector noise—complete with its rare Kunz photocell.

We have also identified a number of instruments and components made by legendary instrument makers,

such as plane and concave gratings ruled by Rowland and Michelson, micrometers by Grubb, Warner

and Swasey, and Fauth, and a variety of lenses and other optics from the workshops of Clarke,

Brashear, and Ross.

The Coblentz thermopile (ca. 1912).

Other important finds include several in the area of early electronic instrumentation. One, the

Coblentz thermopile—a delicate glass device dating from about 1912—was the first detector used to make

accurate measurements of infrared starlight. Another, an elegant string electrometer, was used with

Lick's first photoelectric photometer, built in 1923 by graduate student Elizabeth Cummings. A

third is the Kron-Whitford photometer from about 1930—the first of its type to use an evacuated

chamber to reduce detector noise—complete with its rare Kunz photocell.

We have also identified a number of instruments and components made by legendary instrument makers,

such as plane and concave gratings ruled by Rowland and Michelson, micrometers by Grubb, Warner

and Swasey, and Fauth, and a variety of lenses and other optics from the workshops of Clarke,

Brashear, and Ross.

Related Collections: Publications and Manuscripts, Photographic Plates

In 1966 Lick headquarters moved from Mount Hamilton to the University's newly established

campus at Santa Cruz. At the same time, Mary Lea Shane, astronomer and wife of former observatory

director C. Donald Shane, set out to preserve and organize the written records documenting the

observatory's construction and day-to-day operation, astronomers' personal papers, correspondence,

and scientific writings, and many historical photographs. Thanks to her work, these materials are

now preserved in the Mary Lea Shane Archive, in Special Collections at the University of

California Santa Cruz's McHenry Library.

Drawers of plates in the photographic archive.

Drawers of plates in the photographic archive.

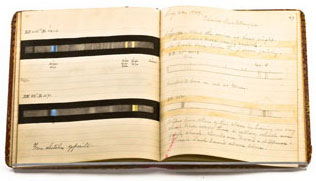

Notebooks in the manuscript collection.

However, two historically important collections of written and photographic material, closely

related to the scientific objects, remain on Mount Hamilton. The first, which we have called

publications and manuscripts, consists of books and offprints (primarily Lick Observatory

publications) and astronomers' notebooks. The second, the photographic plate archive, is among the

largest collections of astronomical plates in the world. It contains spectrograms and direct images

made with every Lick instrument of the photographic era.

As the most vulnerable collection, the scientific objects are the project's first priority,

but safeguarding and publishing the other collections, in whole or in part, is underway in

parallel. Although the approach to each collection differs, the tools for cataloging them are similar,

very much reducing the overhead for the related collections. For example, the underlying

database design for cataloging publications and manuscripts, the forms used for data entry, and

the code supporting online searches all borrow heavily from the tools already developed for

cataloging the scientific objects.

Notebooks in the manuscript collection.

However, two historically important collections of written and photographic material, closely

related to the scientific objects, remain on Mount Hamilton. The first, which we have called

publications and manuscripts, consists of books and offprints (primarily Lick Observatory

publications) and astronomers' notebooks. The second, the photographic plate archive, is among the

largest collections of astronomical plates in the world. It contains spectrograms and direct images

made with every Lick instrument of the photographic era.

As the most vulnerable collection, the scientific objects are the project's first priority,

but safeguarding and publishing the other collections, in whole or in part, is underway in

parallel. Although the approach to each collection differs, the tools for cataloging them are similar,

very much reducing the overhead for the related collections. For example, the underlying

database design for cataloging publications and manuscripts, the forms used for data entry, and

the code supporting online searches all borrow heavily from the tools already developed for

cataloging the scientific objects.

Publications and Manuscripts

Volunteers Paul and Ron Bricmont working with the publications.

In keeping with the practice of the time, Lick Observatory began, from its outset, to publish

articles and monographs under its own imprint describing the work of the observatory. Volume I of

the Publications of the Lick Observatory appeared in 1887. These were joined by two other

series: Contributions from the Lick Observatory beginning in 1889 and Lick Observatory

Bulletins in 1900. Other Lick publications included Director's reports, sixteen editions of

A Brief Account of the Lick Observatory, and occasional monographs appearing as separate

titles. Many articles by Lick astronomers, often those describing new instrumentation, also

appeared in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, a journal with

close ties to the observatory.

Lick Observatory's extensive library—housed for many years on Mount Hamilton and including

long runs of every major astronomical journal and observatory publication, as well as thousands of

individual volumes—became the core of the astronomical collection at UCSC's Natural Sciences

Library (the rarest works are preserved in Special Collections). However, copies of

most Lick publications—offprints, reprints, and bound volumes—were left on the

mountain.

Also remaining on Mount Hamilton is the collection of handwritten observing logs and reduction

books containing astronomers' notes and drawings made at the telescope, and later notes and

calculations made for data analysis. The practice at Lick was for each astronomer to record

his or her own series of observing logs, which would eventually join the others on

the shelf. Some astronomers are represented by only a few books, others filled dozens. These include

nightly observing records and data reduction books, as well as eclipse expeditions logs, logbooks

for some individual telescopes and instruments, and meteorological records.

Volunteers Paul and Ron Bricmont working with the publications.

In keeping with the practice of the time, Lick Observatory began, from its outset, to publish

articles and monographs under its own imprint describing the work of the observatory. Volume I of

the Publications of the Lick Observatory appeared in 1887. These were joined by two other

series: Contributions from the Lick Observatory beginning in 1889 and Lick Observatory

Bulletins in 1900. Other Lick publications included Director's reports, sixteen editions of

A Brief Account of the Lick Observatory, and occasional monographs appearing as separate

titles. Many articles by Lick astronomers, often those describing new instrumentation, also

appeared in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, a journal with

close ties to the observatory.

Lick Observatory's extensive library—housed for many years on Mount Hamilton and including

long runs of every major astronomical journal and observatory publication, as well as thousands of

individual volumes—became the core of the astronomical collection at UCSC's Natural Sciences

Library (the rarest works are preserved in Special Collections). However, copies of

most Lick publications—offprints, reprints, and bound volumes—were left on the

mountain.

Also remaining on Mount Hamilton is the collection of handwritten observing logs and reduction

books containing astronomers' notes and drawings made at the telescope, and later notes and

calculations made for data analysis. The practice at Lick was for each astronomer to record

his or her own series of observing logs, which would eventually join the others on

the shelf. Some astronomers are represented by only a few books, others filled dozens. These include

nightly observing records and data reduction books, as well as eclipse expeditions logs, logbooks

for some individual telescopes and instruments, and meteorological records.

Volunteer Andy Macica with the manuscript collection's observing logs.

As with the scientific objects, no complete inventory of publications or manuscripts exists, much

less a proper catalog, but work is under way to correct this. The manuscript collection contains over

two thousand volumes, mostly observing logs and reduction books. They are unique and vulnerable,

until now existing only in the original. An electronic inventory is well underway, and the most

interesting and important of the logbooks are being photographed, page by page, at high resolution.

The publications are not unique (though some have unique provenance) and many of the articles are

available in digital form through the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System's digital library portal.

Nevertheless, a nearly complete physical collection of Lick publications, many of them describing

Lick instruments or reporting results obtained with them, is a welcome complement to the scientific

objects, manuscripts, and photographic plates. Work on a searchable database of publications has begun,

and in a few cases including digital copies where works are otherwise unavailable or where improved

copies are needed.

Volunteer Andy Macica with the manuscript collection's observing logs.

As with the scientific objects, no complete inventory of publications or manuscripts exists, much

less a proper catalog, but work is under way to correct this. The manuscript collection contains over

two thousand volumes, mostly observing logs and reduction books. They are unique and vulnerable,

until now existing only in the original. An electronic inventory is well underway, and the most

interesting and important of the logbooks are being photographed, page by page, at high resolution.

The publications are not unique (though some have unique provenance) and many of the articles are

available in digital form through the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System's digital library portal.

Nevertheless, a nearly complete physical collection of Lick publications, many of them describing

Lick instruments or reporting results obtained with them, is a welcome complement to the scientific

objects, manuscripts, and photographic plates. Work on a searchable database of publications has begun,

and in a few cases including digital copies where works are otherwise unavailable or where improved

copies are needed.

James Keeler's observing logbook from August, 1889.

James Keeler's observing logbook from August, 1889.

Photographic Plates

The size of the photographic plate collection (we estimate about 150,000 plates) puts systematic

cataloging beyond the scope of the project. Moreover, while the collection taken as a whole is a

monument to the observing enterprise, taken individually, only certain plates are

historically important. (N.B. A plate's scientific value does not depend on its historical

significance. Many plates may contain useful archival data without having special historical

importance.)

Glass-plate spectrograms in the photographic archive.

Glass-plate spectrograms in the photographic archive.

Region of the Milky Way by E. E. Barnard (ca. 1895).

However, scanning and publishing a selection of plates of outstanding historical and/or aesthetic

value falls within the aims of the historical collections project. These include, among others, Barnard's

Milky Way and comet images, Keeler's Crossley plates of spiral nebulae, E. S. Holden's moon plates,

David Todd's 1882 transit of Venus plates, eclipse coronas, the 1922 Einstein-effect fields, and

views of Lick eclipse camps. Furthermore, the collection contains examples of virtually every species

of astrophotograph, spanning the entire era of astrophotography's predominance in research, making

it an invaluable resource and teaching tool for the history of astronomy.

Region of the Milky Way by E. E. Barnard (ca. 1895).

However, scanning and publishing a selection of plates of outstanding historical and/or aesthetic

value falls within the aims of the historical collections project. These include, among others, Barnard's

Milky Way and comet images, Keeler's Crossley plates of spiral nebulae, E. S. Holden's moon plates,

David Todd's 1882 transit of Venus plates, eclipse coronas, the 1922 Einstein-effect fields, and

views of Lick eclipse camps. Furthermore, the collection contains examples of virtually every species

of astrophotograph, spanning the entire era of astrophotography's predominance in research, making

it an invaluable resource and teaching tool for the history of astronomy.

The Historical Collections Project as Museum

The Historical Collections Project is, in effect, a museum. Interpreting and presenting its holdings

is a natural part of its mission.

Nineteenth century eyepieces.

The collections present rich opportunities for the development of online exhibits. The number

of topics is almost inexhaustible, have the potential to reach large and

diverse audiences, and can serve as teaching tools. They cost a fraction of their physical

counterparts in museums, and because a virtual exhibit does not require physical exhibition space,

it need never be taken down to make room for the next one.

Nineteenth century eyepieces.

The collections present rich opportunities for the development of online exhibits. The number

of topics is almost inexhaustible, have the potential to reach large and

diverse audiences, and can serve as teaching tools. They cost a fraction of their physical

counterparts in museums, and because a virtual exhibit does not require physical exhibition space,

it need never be taken down to make room for the next one.

Nevertheless, for all their important uses and advantages, virtual exhibits cannot inspire the same sense of wonder that comes with being in the presence of an important or beautiful artifact. The combined historical collections contain the raw materials for actual displays, and their development is another longterm aim of the Historical Collections Project.

Museums preserve as well as present. People with firsthand knowledge of the artifacts in the scientific objects collection, gained from their development and use, and those with expertise in the now nearly defunct field of research astrophotography are a vanishing resource. Digital detectors (1979- ca. 1994).

Those who used Lick's early telescopes and instruments are of course long gone, and few personal

and anecdotal accounts of their use survive. Had the future historic importance of these objects

been recognized at the time, we would likely have more such records. We can, however, take the

obvious lesson to heart and aim to preserve firsthand knowledge while we can. To this end,

the Historical Collections Project aims to record oral histories from the people with this knowledge.

Museums also provide a focus for scholarship. The combined Lick collections contain an abundance of

materials inviting historical research. Because the collections are little known, their use by

scholars has thus far been less than their contents merit. Lack of a catalog and difficulty of

access have added to the collections' underutilization. Despite these obstacles, materials from the

collections—especially the photographic plate archive, which is a little more widely

known—have provided historians and other scholars with materials over the years. Simply by

raising awareness of the collections, the Project will promote their scholarly use, while the online

catalogs will greatly enhance their usefulness for researchers.

Digital detectors (1979- ca. 1994).

Those who used Lick's early telescopes and instruments are of course long gone, and few personal

and anecdotal accounts of their use survive. Had the future historic importance of these objects

been recognized at the time, we would likely have more such records. We can, however, take the

obvious lesson to heart and aim to preserve firsthand knowledge while we can. To this end,

the Historical Collections Project aims to record oral histories from the people with this knowledge.

Museums also provide a focus for scholarship. The combined Lick collections contain an abundance of

materials inviting historical research. Because the collections are little known, their use by

scholars has thus far been less than their contents merit. Lack of a catalog and difficulty of

access have added to the collections' underutilization. Despite these obstacles, materials from the

collections—especially the photographic plate archive, which is a little more widely

known—have provided historians and other scholars with materials over the years. Simply by

raising awareness of the collections, the Project will promote their scholarly use, while the online

catalogs will greatly enhance their usefulness for researchers.

Project Staff

Project staff, clockwise from upper right, volunteers Ron Bricmont, Paul

Bricmont, Marianne Guntow, and Patrick Maloney; at center, Tony Misch, project director; not shown: Andy Macica.

The Historical Collections Project is directed by former Lick Observatory support astronomer,

Tony Misch. The ongoing work of the project would not be possible without a core group of

volunteers who have contributed skills in database management, photography, and web development, and

devoted many hours to the creation of infrastructure and all aspects of cataloging.

The Project owes much to the support and assistance of members of the Lick Observatory

staff both on Mount Hamilton and in Santa Cruz. We would also like to thank Adobe Corporation for

their generous donation of software.

To contact the Project, please send email to collections@ucolick.org.

Project staff, clockwise from upper right, volunteers Ron Bricmont, Paul

Bricmont, Marianne Guntow, and Patrick Maloney; at center, Tony Misch, project director; not shown: Andy Macica.

The Historical Collections Project is directed by former Lick Observatory support astronomer,

Tony Misch. The ongoing work of the project would not be possible without a core group of

volunteers who have contributed skills in database management, photography, and web development, and

devoted many hours to the creation of infrastructure and all aspects of cataloging.

The Project owes much to the support and assistance of members of the Lick Observatory

staff both on Mount Hamilton and in Santa Cruz. We would also like to thank Adobe Corporation for

their generous donation of software.

To contact the Project, please send email to collections@ucolick.org.