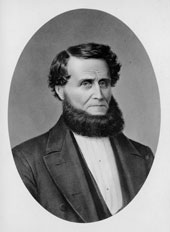

James Lick, the "Generous Miser"

He was an honest, industrious man, of much common

sense, though noted for many eccentricities and whims and in his later years,

of irritable and thoroughly disagreeable temperament....His great and

well merited fame rests on the final disposition of his millions,

which after provision for his relatives, were devoted to various

scientific, charitable, and educational enterprises for the benefit

of the donor's adopted state.

Hubert H. Bancroft in Rosemary Lick's The Generous Miser

"A telescope superior to and more

powerful than any telescope yet made ... and also a suitable

observatory connected therewith ..."

The Story of Lick Observatory begins at

a time of rapid change in the American West. The new transcontinental

railroad had only recently linked the young state of California to the

established centers of science and commerce in the East. The Gold Rush

had left a profoundly changed economy in its wake. Fortunes had been

made, and among those who had reaped the wealth was a thrifty

Pennsylvania Dutchman who had found gold not in the foothills of the

Sierra Nevada, but in the booming real estate market fueled by

California's unprecedented growth.

Even as he lay dying in the sumptuous San Francisco hotel he

had built, James Lick was issuing final orders for the

disposition of his fortune. His largest single bequest would

be for construction of the astronomical observatory that

bears his name. The telescope he envisioned - part high-

visibility scientific enterprise, part monument to himself -

was to be second to none. But first, Lick's own extraordinary

story, from Pennsylvania woodworker to California

millionaire, bears telling.

from James Lick's deed of trust, 1874

Some day, I will own a mill that will make yours

look like a pigsty!

James Lick was born in Stumpstown (now Fredericksburg),

Pennsylvania, on August 25th, 1796, the eldest of seven

children. His father was a skilled woodworker and on his thirteenth

birthday James became his apprentice, learning carpentry and

cabinetmaking under the master's stern and demanding

tutelage. He was a quiet and obedient pupil who, despite any

inward resentment he may have harbored against his father's

severity, strove to achieve the excellence that was expected

of him. In time, his skill became equal to that of his

teacher's.

James might have settled into an unremarkable existence in

Stumpstown, working the family farm and building fine cedar

chests for the local trade, but, at the age of 21, an

ill-starred romance changed the course of his life. Rosemary Lick tells

the story in The Generous Miser, her biography of her great-granduncle:

"He had been keeping company with a girl named Barbara Snavely for some time.

She was the daughter of a local miller and farmer. James was very much in

love with Barbara. One day, she confided to him that she was pregnant.

He became very concerned and planned to do the right thing by marrying her

immediately. However, when he talked to her father the next day, and

asked his permission to marry Barbara, Henry Snavely was indignant at the

very idea of a young apprentice joiner having the temerity to ask for his

daughter's hand in marriage.

'Have you a penny in your purse?' he asked James. Without even waiting

for an answer, he went on. 'When you own a mill as large and costly as

mine, you can have my daughter's hand, but not before.'

An angry James strode from the house, but before he left, he shot back

at the haughty miller, 'Some day, I will own a mill that will make yours

look like a pigsty!'"

Following his disappointment, Lick left Stumpstown. He found

work in Baltimore where he learned the art of piano making,

and before long set up his own shop in New York. In 1821,

after learning that his pianos were being exported to South

America, Lick packed his tools, his workbench, and his few

belongings, and sailed for Argentina, reasoning that by

taking himself to the market he could more quickly build the

fortune he needed to win the hand of his beloved Barbara.

South American Years

Nineteenth century Buenes Aires.

Lick's South American years - nearly thirty in all - were

prosperous and colorful ones. He established his first

workshop in Buenos Aires where his honesty and fine

craftsmanship soon placed him in high regard. The business

prospered despite chronic - and often violent - political

turmoil.

At first Lick found his new life difficult. He was frequently

ill and was handicapped by his lack of Spanish. He had

arrived during a particularly unstable period and was unhappy

witness to bloody uprisings in the city. In 1825, even with

his business thriving and command of the language attained,

Lick wrote to his father that he was "one minute in the

clouds of heaven and the next in the depths of the sea and

death always before my eyes in ten thousand forms. This is

far from peaceful living", he continued, "and I would not

wish it on my worst enemy."

That same year, leaving his business in the hands of a

trusted man, Lick left for a year's tour of Europe, hoping to

regain health and peace of mind. On the return voyage, his

ship, after nearly sinking in a fearsome storm, was captured

by a Portuguese Man-o-War as it approached Buenos Aires.

Passengers and crew were taken to Montevideo (in present-day

Uruguay) as prisoners of war. Lick's daring escape on foot

finally brought him home, where he found his business much in

need of attention.

Lick immediately set about reestablishing his fortune. He

soon restored his piano business to its former prosperity,

and began a lucrative trade in furs. By 1832 he felt that he

had accumulated enough money to make the long hoped-for trip

back to Stumpstown, to at last claim the bride he expected to

find waiting. However, despite the $40,000 he carried, Lick

saw neither his would-be bride nor his son. On hearing of her

old lover's imminent return, Barbara, who had married another

man only two years after Lick's departure, had taken their

son John and left Stumpstown. Though James had

corresponded with his family, he had apparently not

communicated his intention to return for Barbara, and no one

had informed him of her marriage.

Nineteenth century Buenes Aires.

Lick's South American years - nearly thirty in all - were

prosperous and colorful ones. He established his first

workshop in Buenos Aires where his honesty and fine

craftsmanship soon placed him in high regard. The business

prospered despite chronic - and often violent - political

turmoil.

At first Lick found his new life difficult. He was frequently

ill and was handicapped by his lack of Spanish. He had

arrived during a particularly unstable period and was unhappy

witness to bloody uprisings in the city. In 1825, even with

his business thriving and command of the language attained,

Lick wrote to his father that he was "one minute in the

clouds of heaven and the next in the depths of the sea and

death always before my eyes in ten thousand forms. This is

far from peaceful living", he continued, "and I would not

wish it on my worst enemy."

That same year, leaving his business in the hands of a

trusted man, Lick left for a year's tour of Europe, hoping to

regain health and peace of mind. On the return voyage, his

ship, after nearly sinking in a fearsome storm, was captured

by a Portuguese Man-o-War as it approached Buenos Aires.

Passengers and crew were taken to Montevideo (in present-day

Uruguay) as prisoners of war. Lick's daring escape on foot

finally brought him home, where he found his business much in

need of attention.

Lick immediately set about reestablishing his fortune. He

soon restored his piano business to its former prosperity,

and began a lucrative trade in furs. By 1832 he felt that he

had accumulated enough money to make the long hoped-for trip

back to Stumpstown, to at last claim the bride he expected to

find waiting. However, despite the $40,000 he carried, Lick

saw neither his would-be bride nor his son. On hearing of her

old lover's imminent return, Barbara, who had married another

man only two years after Lick's departure, had taken their

son John and left Stumpstown. Though James had

corresponded with his family, he had apparently not

communicated his intention to return for Barbara, and no one

had informed him of her marriage.

The brig Lady Adams.

Disheartened, Lick returned to Buenos Aires, but with

revolution threatening, soon moved to Valparaiso, Chile.

Four years later, again to escape the clouds of war, he moved

to his third and last South American home: Lima, Peru. As

before, his high standards established his good reputation

and his services were soon in great demand.

Lick spent a prosperous decade in Lima, but by 1846 he had

made up his mind to return to North America. Always an avid

reader of newspapers and observer of the political scene, he

had watched the dispute between Mexico and the United States

over Texan sovereignty arise, and had concluded that war was

inevitable. Lick fully expected a U.S. victory and with it

the annexation of California, a territory rich with

opportunity for a man with vision - and capital to back it.

Once having made up his mind, Lick was anxious to leave, but

his mostly Mexican workers had quit to fight in the war which

had broken out in April of 1846, leaving him with a dozen

unfilled orders. In characteristic fashion, Lick remained in

Lima another eighteen months, finishing the pianos with his

own hands. Finally, his obligations discharged, he sailed for

California on the brig Lady Adams in November, 1847.

The brig Lady Adams.

Disheartened, Lick returned to Buenos Aires, but with

revolution threatening, soon moved to Valparaiso, Chile.

Four years later, again to escape the clouds of war, he moved

to his third and last South American home: Lima, Peru. As

before, his high standards established his good reputation

and his services were soon in great demand.

Lick spent a prosperous decade in Lima, but by 1846 he had

made up his mind to return to North America. Always an avid

reader of newspapers and observer of the political scene, he

had watched the dispute between Mexico and the United States

over Texan sovereignty arise, and had concluded that war was

inevitable. Lick fully expected a U.S. victory and with it

the annexation of California, a territory rich with

opportunity for a man with vision - and capital to back it.

Once having made up his mind, Lick was anxious to leave, but

his mostly Mexican workers had quit to fight in the war which

had broken out in April of 1846, leaving him with a dozen

unfilled orders. In characteristic fashion, Lick remained in

Lima another eighteen months, finishing the pianos with his

own hands. Finally, his obligations discharged, he sailed for

California on the brig Lady Adams in November, 1847.

A New Life in California

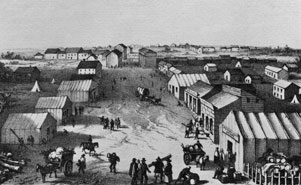

San Francisco at about the time

of Lick's arrival.

Lick arrived in San Francisco in January, 1848, less than a

month before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded California

to the United States. He brought his tools, his workbench,

and an iron-clad chest containing $30,000 in Peruvian gold.

(Lick's baggage also included 600 pounds of chocolate

purchased from his confectioner neighbor in Lima. The

chocolate sold quickly, and, on Lick's advice, the

confectioner - Domingo Ghirardelli - moved to San Francisco, where

his name is synonymous with the city to this day!)

Lick looked at the hills and mudflats of the little shanty

town with its thousand inhabitants and fine natural harbor,

and saw in it a thriving city and a center of commerce. He

at once began to turn his cash into land. He bought shrewdly

and without hesitation, acquiring thirty-seven lots by mid-March.

Lick's unprecedented buying spree was the talk of San

Francisco, and surely many locals, thinking him a bit

touched, must have been only too glad to take his money.

What Lick and his fellow San Franciscans could not have

foreseen was an event which would change the course of

California history and completely reshape her economy. The

discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill, only seventeen days after

Lick's arrival, would soon give rise to a boom which

catapulted San Francisco's population to twenty thousand in

the next two years.

San Francisco at about the time

of Lick's arrival.

Lick arrived in San Francisco in January, 1848, less than a

month before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded California

to the United States. He brought his tools, his workbench,

and an iron-clad chest containing $30,000 in Peruvian gold.

(Lick's baggage also included 600 pounds of chocolate

purchased from his confectioner neighbor in Lima. The

chocolate sold quickly, and, on Lick's advice, the

confectioner - Domingo Ghirardelli - moved to San Francisco, where

his name is synonymous with the city to this day!)

Lick looked at the hills and mudflats of the little shanty

town with its thousand inhabitants and fine natural harbor,

and saw in it a thriving city and a center of commerce. He

at once began to turn his cash into land. He bought shrewdly

and without hesitation, acquiring thirty-seven lots by mid-March.

Lick's unprecedented buying spree was the talk of San

Francisco, and surely many locals, thinking him a bit

touched, must have been only too glad to take his money.

What Lick and his fellow San Franciscans could not have

foreseen was an event which would change the course of

California history and completely reshape her economy. The

discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill, only seventeen days after

Lick's arrival, would soon give rise to a boom which

catapulted San Francisco's population to twenty thousand in

the next two years.

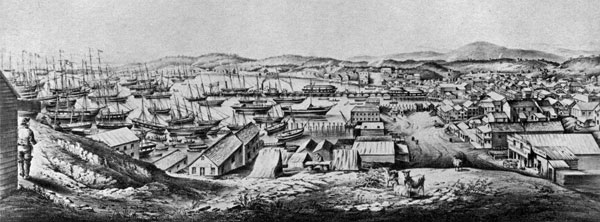

San Francisco about 1850.

Even the conservative Lick was infected with gold fever, but

a week in the mud of the gold fields convinced him that his

future lay not in the glittering metal beneath the soil but

in the land itself. By prompt and judicious investment he

was able to purchase sizeable real estate holdings at a time

when many residents were anxious to sell in order to seek

treasure in the gold-laden foothills. This "buyer's market"

allowed Lick to purchase more land than he might otherwise

have done. While luck certainly played a role in creating

these circumstances, Lick possessed the intelligence,

courage, and capital to take full advantage of the

opportunity.

Now in his mid-fifties, tall, vigorous, and stern, his strong

face framed with a severe beard and a head of thick dark

hair, Lick was an imposing figure. As his wealth and holdings

increased, his interest turned more and more to the land. He

left the management of his San Francisco properties to an

agent, and focused his attention on a large tract of land he

owned near San Jose. He gave rein to his gift for

horticulture, transforming his orchards into some of the

finest in the state and selling produce to the hungry

residents of San Francisco.

San Francisco about 1850.

Even the conservative Lick was infected with gold fever, but

a week in the mud of the gold fields convinced him that his

future lay not in the glittering metal beneath the soil but

in the land itself. By prompt and judicious investment he

was able to purchase sizeable real estate holdings at a time

when many residents were anxious to sell in order to seek

treasure in the gold-laden foothills. This "buyer's market"

allowed Lick to purchase more land than he might otherwise

have done. While luck certainly played a role in creating

these circumstances, Lick possessed the intelligence,

courage, and capital to take full advantage of the

opportunity.

Now in his mid-fifties, tall, vigorous, and stern, his strong

face framed with a severe beard and a head of thick dark

hair, Lick was an imposing figure. As his wealth and holdings

increased, his interest turned more and more to the land. He

left the management of his San Francisco properties to an

agent, and focused his attention on a large tract of land he

owned near San Jose. He gave rein to his gift for

horticulture, transforming his orchards into some of the

finest in the state and selling produce to the hungry

residents of San Francisco.

Eccentric Millionaire

Lick mill, Santa Clara, CA.

Though 37 years had passed since Lick's angry confrontation

with Henry Snavely, Lick had not forgotten his bitter promise

to the miller. Along the banks of the Guadalupe river, he

built the mill that would make Snavely's "look like a

pigsty." Lick did much of the work himself on the lavish

$200,000 project, which came to be known, for its extravagant

use of the most costly machinery and the finest woods, as

"the Mahogany Mill" and "Lick's Folly."

When the mill was finally completed in 1855, Lick had it

photographed and copies sent to Stumpstown. Though in all

likelihood Henry Snavely was dead by that time, this did not

stop the proud Lick from making good on his promise of thirty-five

years before.

That same year Lick sent for his son John, who, at thirty-

seven, had never met his father. He brought with him the

news that his mother, Barbara, had died four years before.

John remained with his father for eight years, but the

relationship was not an easy one. Though Lick made his son

manager of the mill, he thought him irresponsible and without

ambition.

At first, Lick and his son shared a small cabin. In hopes of

improving their relationship, Lick built a colonial mansion

with a marble fireplace in each of its 24 rooms, but, to his

great disappointment, John preferred the simplicity of the

cabin. Soon Lick himself lost interest in the project. He

never furnished the grand house, sleeping instead on an old

door propped between two nail kegs, and drying fruit from his

orchards on newspapers spread in the empty rooms. In 1863,

John went back to Pennsylvania, returning only when his

father was on his deathbed.

Though known - and sometimes criticized - for his austere

personal habits, Lick was capable of vision on a grand scale.

Late in 1861 he began work on a hotel in San Francisco that

came to be regarded as the finest west of the Mississippi.

The dining room, with its seating for 400, was modeled after one

which Lick had seen 35 years before in the palace at

Versailles. Lick meticulously cut and placed much of the

exquisite wood inlay in the dining room with his own hands.

The magnificent hotel, known as Lick House, was destroyed in

the great San Francisco fire which followed the earthquake of

1906.

Lick mill, Santa Clara, CA.

Though 37 years had passed since Lick's angry confrontation

with Henry Snavely, Lick had not forgotten his bitter promise

to the miller. Along the banks of the Guadalupe river, he

built the mill that would make Snavely's "look like a

pigsty." Lick did much of the work himself on the lavish

$200,000 project, which came to be known, for its extravagant

use of the most costly machinery and the finest woods, as

"the Mahogany Mill" and "Lick's Folly."

When the mill was finally completed in 1855, Lick had it

photographed and copies sent to Stumpstown. Though in all

likelihood Henry Snavely was dead by that time, this did not

stop the proud Lick from making good on his promise of thirty-five

years before.

That same year Lick sent for his son John, who, at thirty-

seven, had never met his father. He brought with him the

news that his mother, Barbara, had died four years before.

John remained with his father for eight years, but the

relationship was not an easy one. Though Lick made his son

manager of the mill, he thought him irresponsible and without

ambition.

At first, Lick and his son shared a small cabin. In hopes of

improving their relationship, Lick built a colonial mansion

with a marble fireplace in each of its 24 rooms, but, to his

great disappointment, John preferred the simplicity of the

cabin. Soon Lick himself lost interest in the project. He

never furnished the grand house, sleeping instead on an old

door propped between two nail kegs, and drying fruit from his

orchards on newspapers spread in the empty rooms. In 1863,

John went back to Pennsylvania, returning only when his

father was on his deathbed.

Though known - and sometimes criticized - for his austere

personal habits, Lick was capable of vision on a grand scale.

Late in 1861 he began work on a hotel in San Francisco that

came to be regarded as the finest west of the Mississippi.

The dining room, with its seating for 400, was modeled after one

which Lick had seen 35 years before in the palace at

Versailles. Lick meticulously cut and placed much of the

exquisite wood inlay in the dining room with his own hands.

The magnificent hotel, known as Lick House, was destroyed in

the great San Francisco fire which followed the earthquake of

1906.

The dining room at Lick House

Another of his grand enterprises - a replica of the iron and

glass conservatory in London's Kew Gardens which he had

ordered from an East Coast firm - was intended as a gift to the

city of San Jose, but when Lick read an article in a local

newspaper criticizing his characteristically shabby dress, he

withdrew the gift, never opening the crates in which it had

arrived. After Lick's death, the impressive structure was

purchased by a group of San Franciscans who assembled it in

Golden Gate Park where it still stands as the beautiful

Conservatory of Flowers.

Lick was widely known for his eccentricity. He showed little

interest in his own comfort or appearance. He was laconic and

taciturn and rarely felt the need to explain himself to those

around him. He was known to test the obedience of his workers

by assigning such tasks as planting trees upside-down. He

enjoyed showing off his orchards and flowers to visitors, but

once, overhearing one of a group of young ladies remark that

she had seen prettier violas in San Francisco, he stranded

them in a field, leaving them to find their own way home.

He could be both generous and miserly, thoughtful and

inflexible. Though he had invited his son to share his life

and fortune, he later all but cut him from his will, citing

John's neglect of his pet parrot. He is said to have offered

a 60-acre field to a stranger for the cost of the fence, but

when the man took a day to decide, Lick told him that because

he had wavered he could no longer have the land at any price.

The dining room at Lick House

Another of his grand enterprises - a replica of the iron and

glass conservatory in London's Kew Gardens which he had

ordered from an East Coast firm - was intended as a gift to the

city of San Jose, but when Lick read an article in a local

newspaper criticizing his characteristically shabby dress, he

withdrew the gift, never opening the crates in which it had

arrived. After Lick's death, the impressive structure was

purchased by a group of San Franciscans who assembled it in

Golden Gate Park where it still stands as the beautiful

Conservatory of Flowers.

Lick was widely known for his eccentricity. He showed little

interest in his own comfort or appearance. He was laconic and

taciturn and rarely felt the need to explain himself to those

around him. He was known to test the obedience of his workers

by assigning such tasks as planting trees upside-down. He

enjoyed showing off his orchards and flowers to visitors, but

once, overhearing one of a group of young ladies remark that

she had seen prettier violas in San Francisco, he stranded

them in a field, leaving them to find their own way home.

He could be both generous and miserly, thoughtful and

inflexible. Though he had invited his son to share his life

and fortune, he later all but cut him from his will, citing

John's neglect of his pet parrot. He is said to have offered

a 60-acre field to a stranger for the cost of the fence, but

when the man took a day to decide, Lick told him that because

he had wavered he could no longer have the land at any price.

Generous Miser

Despite his eccentricities, Lick is best remembered for his

strong will and determination, his ambition and drive, his

honesty and generosity. Yet there lingers about the edges of

these harder qualities, a shade of resignation, even

fatality. Once, while carrying an ox-yoke on his shoulders,

he was overtaken by a friend with a horse and wagon who

offered him a ride. Lick thanked the man but declined. His

friend then asked if he wouldn't at least put the heavy yoke

in the wagon. "So far in life", he replied, "I have born my

yoke patiently, and I will not shirk my duty now".

One evening in his 77th year, alone in the kitchen of his

Santa Clara homestead, Lick collapsed from a severe stroke.

In the morning he was found, alive but helpless, by his

foreman, Thomas Fraser, a man who, years before, had earned a

job by unquestioningly following Lick's orders to stack and

restack a pile of bricks in the rubble of a burnt house. Lick

lived another three years, but never completely regained his

health.

His estates now included, in addition to many properties in

San Francisco and the Santa Clara Valley, holdings on the

shores of Lake Tahoe, a huge ranch in Los Angeles County, and

all of Santa Catalina Island off the southern California

shore. He was among the richest men in a state noted for its

riches.

Lick's infirmity forced him to move to a room in his San

Francisco hotel, where he could be more easily cared for. It

was there that he turned his attention to the disposition of

his fortune, formulating a variety of bequests ranging from

public baths to a home for aging widows, from a generous

donation to an orphanage to one for the prevention of cruelty

to animals, from the foundation of a vocational school to

monuments honoring his parents and grandfather.

Never far from his mind, however, was the monument he wished

to leave to his own memory. At first, Lick wanted to set

aside a million dollars to erect enormous statues of himself

and his parents, so tall as to be visible far out to sea.

This plan was abandoned when a friend pointed out that the

monumental statues would make vulnerable targets in the event

of a naval bombardment. The scheme was replaced by an even

grander one: a pyramid, larger than the Great Pyramid in

Egypt, to be built in downtown San Francisco upon a block

which he entirely owned! But, to the lasting benefit of

science - if not to the San Francisco tourist trade - Lick's

thoughts were turned from pyramids to telescopes.

Several persons have been credited with sparking Lick's

interest in the stars and steering him in the direction of

building an observatory. According to legend, in 1860, Lick

had met a student of astronomy and itinerant lecturer named

George Madeira who had talked to him of the heavens and

impressed him with views through his small telescope. Madeira

is reputed to have told Lick that "If I had your wealth ... I

would construct the largest telescope possible to construct".

Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who

had met Lick in 1871, also claimed to have guided him towards

a major scientific bequest by holding up the example of his

institution's benefactor, John Smithson.

But the single person most responsible for Lick's eventual

decision to build an observatory was his friend George

Davidson: astronomer, geographer, and President of the

California Academy of Sciences. Davidson often visited the

ailing millionaire in his room at Lick House, and in the

course of their conversations, gently led him to the idea of

his greatest monument.

They discussed science, astronomy, the planets, the rings of Saturn, and

the mountains on the moon. Their talks soon veered to telescopes, and before

long Lick decided to forego his pyramid and instead give his fortune for a

telescope 'superior to and more powerful than any telescope yet made.'

(from Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock, Gustafson, and Unruh).

Text is copyright 1998, Anthony Misch and Remington Stone. Images are copyright University of California and The Mary Lea Shane Archive. The authors are indebted, in particular, to two sources for the material in this essay: Eye on the Sky by Donald Osterbrock, John Gustafson, and W. Shiloh Unruh, University of California Press, 1988, and The Generous Miser by Rosemary Lick, Ward Ritchey Press, 1967.