Building the Observatory

The possibility that a complete

astronomical establishment might one day be planted on the summit seemed

more a fairy tale than a sober fact.

Captain Richard S. Floyd

in the Publications of the Lick Observatory, Volume I, 1887

A Captain at the Helm

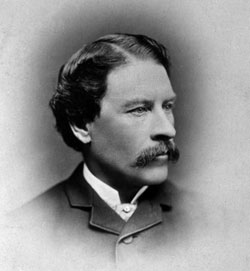

Captain Richard Floyd, president of the Lick Trust.

Shortly before his death in 1876, James Lick,

an adopted son of California and one of the state's wealthiest citizens,

put his name on a deed of trust which, among other bequests, designated a

sum of money for the construction of a telescope "superior to and more

powerful" than any yet made.

Lick's deed of trust did not spell out the details of the new observatory,

leaving the Board of Trust great latitude and a great burden of

responsibility in carrying out his wishes. Its president, and the board

member most responsible for shaping the observatory, was Captain

Richard S. Floyd. Floyd had met Lick in 1874, through the foreman of

Lick's Santa Clara homestead, Thomas Fraser. Lick was immediately impressed by the

younger man, and the following year, to Floyd's surprise, appointed him

to head Lick's second Board of Trust. Surviving its dissolution by the

impatient Lick, Floyd emerged as president of the third and final board.

Richard Floyd was a plantation-raised gentleman, a veteran of the

Confederate navy, a former prisoner of war, a sea captain, and,

at age 31, retired and newly married to the beautiful and wealthy

Cora Lyons. He was a practical man with gifts for art and mathematics

and a position that afforded him the leisure to devote his talent and

energy to building the world's largest telescope. He joined forces with

Fraser, who, as superintendent of construction for the observatory,

brought his skill, inventiveness, and loyalty to the job. Between them,

Floyd and Fraser gave shape to Lick's dream.

Captain Richard Floyd, president of the Lick Trust.

Shortly before his death in 1876, James Lick,

an adopted son of California and one of the state's wealthiest citizens,

put his name on a deed of trust which, among other bequests, designated a

sum of money for the construction of a telescope "superior to and more

powerful" than any yet made.

Lick's deed of trust did not spell out the details of the new observatory,

leaving the Board of Trust great latitude and a great burden of

responsibility in carrying out his wishes. Its president, and the board

member most responsible for shaping the observatory, was Captain

Richard S. Floyd. Floyd had met Lick in 1874, through the foreman of

Lick's Santa Clara homestead, Thomas Fraser. Lick was immediately impressed by the

younger man, and the following year, to Floyd's surprise, appointed him

to head Lick's second Board of Trust. Surviving its dissolution by the

impatient Lick, Floyd emerged as president of the third and final board.

Richard Floyd was a plantation-raised gentleman, a veteran of the

Confederate navy, a former prisoner of war, a sea captain, and,

at age 31, retired and newly married to the beautiful and wealthy

Cora Lyons. He was a practical man with gifts for art and mathematics

and a position that afforded him the leisure to devote his talent and

energy to building the world's largest telescope. He joined forces with

Fraser, who, as superintendent of construction for the observatory,

brought his skill, inventiveness, and loyalty to the job. Between them,

Floyd and Fraser gave shape to Lick's dream.

Astronomer Simon Newcomb.

However, for all of Floyd's capability and enthusiasm, neither he nor

any other member of the board possessed the specialized knowledge needed

to build the observatory. Thus advice was sought from the great astronomical

centers on the east coast of the United States and in Europe. The famous

American astronomer Simon Newcomb of the U.S. Naval Observatory was selected

as Scientific Advisor.

In 1874 Newcomb and, two years later, Floyd (with his wife and three-year-old

daughter Harry, who, ten years later, would lay the cornerstone of the great

telescope's dome), traveled to Europe to confer with the most prominent

astronomers and telescope builders of the time.

Meeting Floyd at the outset of his year-long journey,

Newcomb was skeptical that a man with no professional astronomical training

could meet the challenge that Floyd had taken on, but his doubts would prove

unfounded.

Astronomer Simon Newcomb.

However, for all of Floyd's capability and enthusiasm, neither he nor

any other member of the board possessed the specialized knowledge needed

to build the observatory. Thus advice was sought from the great astronomical

centers on the east coast of the United States and in Europe. The famous

American astronomer Simon Newcomb of the U.S. Naval Observatory was selected

as Scientific Advisor.

In 1874 Newcomb and, two years later, Floyd (with his wife and three-year-old

daughter Harry, who, ten years later, would lay the cornerstone of the great

telescope's dome), traveled to Europe to confer with the most prominent

astronomers and telescope builders of the time.

Meeting Floyd at the outset of his year-long journey,

Newcomb was skeptical that a man with no professional astronomical training

could meet the challenge that Floyd had taken on, but his doubts would prove

unfounded.

Refractor or Reflector?

Crucial decisions needed to be made before work could begin. Chief among them

was the choice of telescope design. In trying to settle this question, Newcomb,

Floyd, and the board found themselves in the middle of the rapidly heating

debate over the comparative merits of refracting and reflecting telescopes.

Alvan Clark and Sons, America's foremost makers of telescope lenses.

Refractors, which employ lenses to focus light, had been the choice of most

astronomers since the invention of the telescope. Yet reflectors, which

use mirrors instead of lenses, were gaining acceptance as mirror making

materials and techniques improved and the reflector's optical advantages

became evident.

Some already saw the reflector as the telescope of the future, but it would

be twenty years before another telescope at Lick Observatory would help

to convince the astronomical world that the future lay with mirrors, and

another ten before the era of large reflectors was truly underway.

In the end the board chose the more conservative path, building what remains

today the world's second largest refractor.

The Cleveland firm of Warner and Swasey was chosen to build the telescope

tube, its mount, and the machinery to operate it. Union Ironworks of San

Francisco received the contract for the huge dome. Casting large, optically

pure glass disks and shaping them into the largest lenses ever made—if

indeed they could be made—presented the most challenging problems.

The exacting work of figuring the lenses was entrusted to the highly respected

optical firm of Alvan Clark and Sons of Massachusetts.

The glass disks for the lenses were to be made by

Charles Feil in Paris, the only firm capable of attempting castings of

the required size and quality.

Their production would ultimately cause years of delay, and prove the near

undoing of the House of Feil.

Alvan Clark and Sons, America's foremost makers of telescope lenses.

Refractors, which employ lenses to focus light, had been the choice of most

astronomers since the invention of the telescope. Yet reflectors, which

use mirrors instead of lenses, were gaining acceptance as mirror making

materials and techniques improved and the reflector's optical advantages

became evident.

Some already saw the reflector as the telescope of the future, but it would

be twenty years before another telescope at Lick Observatory would help

to convince the astronomical world that the future lay with mirrors, and

another ten before the era of large reflectors was truly underway.

In the end the board chose the more conservative path, building what remains

today the world's second largest refractor.

The Cleveland firm of Warner and Swasey was chosen to build the telescope

tube, its mount, and the machinery to operate it. Union Ironworks of San

Francisco received the contract for the huge dome. Casting large, optically

pure glass disks and shaping them into the largest lenses ever made—if

indeed they could be made—presented the most challenging problems.

The exacting work of figuring the lenses was entrusted to the highly respected

optical firm of Alvan Clark and Sons of Massachusetts.

The glass disks for the lenses were to be made by

Charles Feil in Paris, the only firm capable of attempting castings of

the required size and quality.

Their production would ultimately cause years of delay, and prove the near

undoing of the House of Feil.

The First Mountaintop Observatory

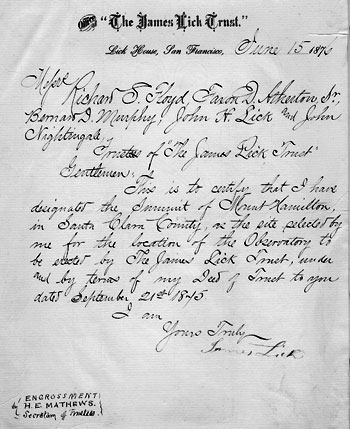

Lick's document designating Mt. Hamilton as the

site for his observatory, June 15, 1876.

In the meantime, beginning in 1874, Lick's Board of Trust began work on

what would be perhaps its single most important decision: selection of the

best possible site for the observatory.

Today we assume that telescopes

will be sited on mountaintops, but at the time of Lick's bequest,

observatories were typically built in cities. Indeed, Lick had originally

envisioned his observatory in San Francisco. However, cities—never the

best location for a telescope—had become increasingly

inhospitable environments for nighttime observing as outdoor

street lights became common and smoke pollution grew. Astronomers were

becoming aware of these problems, so the Board of Trust determined, despite

the daunting logistical problems it presented, to investigate mountaintop

sites for the new telescope. Thus Lick Observatory became the first

permanently occupied mountaintop observatory in the world. Virtually all

others have since followed suit.

Numerous sites were considered. The first tentative choice was on the shores

of Lake Tahoe, but had to be abandoned because deep snows made it inaccessible

in winter. Other peaks were considered, including Mount St. Helena,

in Sonoma County, and various prominent peaks in the San Francisco Bay area.

Finally, in 1875, Lick's foreman Thomas Fraser suggested Mt. Hamilton, after making a

horseback trip to the summit. Although relatively unobtrusive as it nestles

in the Diablo Range to the east of San Jose, Mount Hamilton is the highest

point within a radius of some 85 miles. Its summit had been a familiar sight from

Lick's South Bay ranch, adding to its appeal. Lick

approved of the choice, ending the long search for a suitable site.

Lick's document designating Mt. Hamilton as the

site for his observatory, June 15, 1876.

In the meantime, beginning in 1874, Lick's Board of Trust began work on

what would be perhaps its single most important decision: selection of the

best possible site for the observatory.

Today we assume that telescopes

will be sited on mountaintops, but at the time of Lick's bequest,

observatories were typically built in cities. Indeed, Lick had originally

envisioned his observatory in San Francisco. However, cities—never the

best location for a telescope—had become increasingly

inhospitable environments for nighttime observing as outdoor

street lights became common and smoke pollution grew. Astronomers were

becoming aware of these problems, so the Board of Trust determined, despite

the daunting logistical problems it presented, to investigate mountaintop

sites for the new telescope. Thus Lick Observatory became the first

permanently occupied mountaintop observatory in the world. Virtually all

others have since followed suit.

Numerous sites were considered. The first tentative choice was on the shores

of Lake Tahoe, but had to be abandoned because deep snows made it inaccessible

in winter. Other peaks were considered, including Mount St. Helena,

in Sonoma County, and various prominent peaks in the San Francisco Bay area.

Finally, in 1875, Lick's foreman Thomas Fraser suggested Mt. Hamilton, after making a

horseback trip to the summit. Although relatively unobtrusive as it nestles

in the Diablo Range to the east of San Jose, Mount Hamilton is the highest

point within a radius of some 85 miles. Its summit had been a familiar sight from

Lick's South Bay ranch, adding to its appeal. Lick

approved of the choice, ending the long search for a suitable site.

A view from the summit with Mt. Hamilton Road in the

foreground.

However, not even a trail led up Mt. Hamilton, so a "first-class road to the

summit" to be funded by Santa Clara County was made a condition of the choice

of site. A prominent scientific facility located in what was then an

agricultural district promised considerable prestige for the county, which

promptly agreed to undertake the project at a cost of $70,000. The federal

and state governments granted approximately 2500 acres around and including

the top of Mt. Hamilton to the Board of Trust. Thus, with the building of a

road, began the construction of what was to become the first technological

marvel in the same county which, many years later, would be home to one of

the great technological centers of the modern world, known as Silicon Valley.

The road, which came to be called "Lick Avenue" (now Mt. Hamilton Road), was

completed in 1876. Many who drive it today find the road excessively

winding—and by modern standards it is. But one must bear in mind that

the road was designed for the transport of heavy equipment by horse and wagon.

The slow moving horses didn't mind the many curves, and the grade, which

nowhere exceeds seven percent, suited their labors.

To the frustration of all involved, work on the observatory was then stalled

by a series of legal disputes over the disposition of Lick's estate.

Finally, in 1879, three years after completion of the road, the Board of

Trust hired S. W. Burnham, an accomplished double-star observer, to test the

observing conditions on Mount Hamilton. He visited the mountain in late

summer and early fall—the best months for observing. His glowing report

reinvigorated the project.

A view from the summit with Mt. Hamilton Road in the

foreground.

However, not even a trail led up Mt. Hamilton, so a "first-class road to the

summit" to be funded by Santa Clara County was made a condition of the choice

of site. A prominent scientific facility located in what was then an

agricultural district promised considerable prestige for the county, which

promptly agreed to undertake the project at a cost of $70,000. The federal

and state governments granted approximately 2500 acres around and including

the top of Mt. Hamilton to the Board of Trust. Thus, with the building of a

road, began the construction of what was to become the first technological

marvel in the same county which, many years later, would be home to one of

the great technological centers of the modern world, known as Silicon Valley.

The road, which came to be called "Lick Avenue" (now Mt. Hamilton Road), was

completed in 1876. Many who drive it today find the road excessively

winding—and by modern standards it is. But one must bear in mind that

the road was designed for the transport of heavy equipment by horse and wagon.

The slow moving horses didn't mind the many curves, and the grade, which

nowhere exceeds seven percent, suited their labors.

To the frustration of all involved, work on the observatory was then stalled

by a series of legal disputes over the disposition of Lick's estate.

Finally, in 1879, three years after completion of the road, the Board of

Trust hired S. W. Burnham, an accomplished double-star observer, to test the

observing conditions on Mount Hamilton. He visited the mountain in late

summer and early fall—the best months for observing. His glowing report

reinvigorated the project.

"Burnham had come prepared to like Mount Hamilton ('I am greatly interested

in the place, and have but little doubt, unless there is something very

peculiar in the general location, that the place will prove to be extremely

desirable for astronomical work,' he had written) but the reality exceeded

his expectations. Night after night he recorded in his observing books

remarks such as 'First class seeing. No wind at all,' and 'Splendid

night—absolutely still.'"

(from Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock,

Gustafson, and Unruh).

Construction Begins

Lick's foreman, Thomas Fraser

The actual work of building began in 1880; the overall responsibility for

construction of the observatory was born by Captain Floyd, with Thomas Fraser

as superintendent. Work began with the leveling of the mountaintop.

Lick's foreman, Thomas Fraser

The actual work of building began in 1880; the overall responsibility for

construction of the observatory was born by Captain Floyd, with Thomas Fraser

as superintendent. Work began with the leveling of the mountaintop.

"Fraser and a crew of thirteen men began blasting the top from Mount Hamilton's

steep peak to create a level spot for the observatory's Main Building. 'Every

square foot of available surface [created] involved the removal of a prism of

hard rock one foot on the base and from 10 to 32 feet high,' Floyd later wrote.

Nearly a ton of black powder went to the job, and all told nearly 70,000 tons

of rock were blasted free and moved by hand to clear the top."

(from Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock, Gustafson,

and Unruh).

Construction of the Main Building was simplified when Fraser unearthed a bed

of fine clay about a mile from the summit. Kilns were built near the deposit,

and more than three million bricks were fired, at the rate of 10,000 a day.

Even more important was his discovery of a spring near the summit, which could

provide much needed water for drinking and for water power, eliminating the

long haul from Smith Creek, six miles down the road.

The 12-inch dome in 1881, before construction of the Main Building.

The plan for the Main Building called for two domes, the larger of which would

house the Great Refractor, connected by a long hallway flanked by offices,

laboratories, and a library. First, the smaller dome began to rise on

its cylindrical tower of bricks. By 1881, the small dome was completed and a

12-inch telescope installed. The 12-inch, purchased secondhand from Alvan

Clark's workshop, began its nearly century-long career that same year,

recording a transit of Mercury which launched scientific research on Mt.

Hamilton seven years before the Great Refractor would see first light.

From the side of the 12-inch dome, the long central hallway of the

building began to emerge, advancing southward along the summit as

construction progressed, finally reaching the point where it was to meet

the 36-inch dome. And there it stalled. At the House of Feil in Paris,

one of the disks of glass that would be used to make the giant lens had been

accidentally broken during shipment. Success in reproducing the broken element

proved elusive, and without the glass from Paris, the Clarks could not estimate

the final focal length, without which the final length of the telescope could not

be determined. With the

length of the telescope unknown, construction of its dome could not begin.

The 12-inch dome in 1881, before construction of the Main Building.

The plan for the Main Building called for two domes, the larger of which would

house the Great Refractor, connected by a long hallway flanked by offices,

laboratories, and a library. First, the smaller dome began to rise on

its cylindrical tower of bricks. By 1881, the small dome was completed and a

12-inch telescope installed. The 12-inch, purchased secondhand from Alvan

Clark's workshop, began its nearly century-long career that same year,

recording a transit of Mercury which launched scientific research on Mt.

Hamilton seven years before the Great Refractor would see first light.

From the side of the 12-inch dome, the long central hallway of the

building began to emerge, advancing southward along the summit as

construction progressed, finally reaching the point where it was to meet

the 36-inch dome. And there it stalled. At the House of Feil in Paris,

one of the disks of glass that would be used to make the giant lens had been

accidentally broken during shipment. Success in reproducing the broken element

proved elusive, and without the glass from Paris, the Clarks could not estimate

the final focal length, without which the final length of the telescope could not

be determined. With the

length of the telescope unknown, construction of its dome could not begin.

First Light

Months of waiting turned into

years, but finally, late in 1885, after eighteen failed attempts, a suitable piece of

glass was on its way to Boston. A year later, the largest lenses ever

made crossed the continent on a specially designed railroad car, making the last

leg of the journey by horse and wagon, arriving safely on the summit two days after

Christmas, 1886. With the lenses on hand, construction of the great dome could finally

begin.

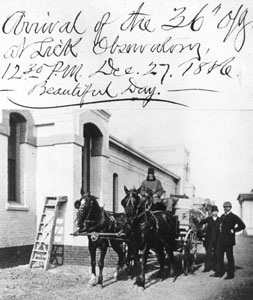

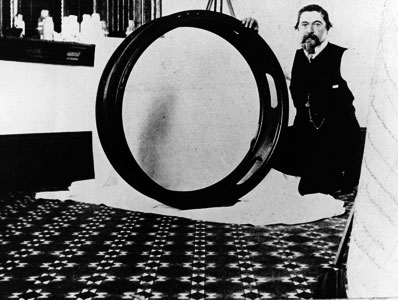

Arrival of the 36-inch lens, 1886.

Arrival of the 36-inch lens, 1886.

Captain Floyd with the newly arrived 36-inch lens.

Captain Floyd with the newly arrived 36-inch lens.

"One evening early in 1886, the Floyds, the Frasers, and the work crew

gathered for a modest ceremony in which Harry Floyd [then 13] laid the

cornerstone for the dome. In the following days Fraser and his crew

began laying out a circle 235 feet around, and then raising skyward,

row by row, a thick wall of bricks for supporting the dome.

By the summer of 1886, Fraser and his workmen had completed the

outer brick walls. They next laid the foundation for the telescope's

support pier. This foundation was constructed to serve a second,

special purpose as well: to hold the body of James Lick."

Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock, Gustafson, and Unruh).

Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock, Gustafson, and Unruh).

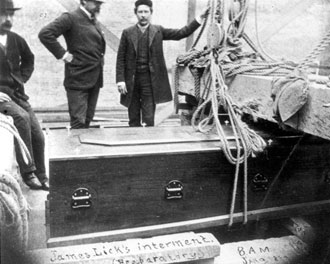

Lick's reinterment in the pier of the 36-inch Refractor, 1887.

Lick's funeral, ten years earlier, had been as grand as that for any head

of state. Flags in San Francisco flew at half staff for three days, while

thousands came to view his body. Hundreds followed the hearse,

drawn by four black horses, through the streets of the city to his resting

place in the Masonic cemetery. But early in January 1887, in

accordance with his wishes and at the appropriate stage in the

construction, James Lick was brought, for the first time, to the summit

of Mt. Hamilton, and laid to rest, for the last time, at the base of the

pier, hidden from sight beneath the floor of his great telescope. A

simple plaque inscribed with the words "Here Lies the Body of James

Lick" is the tomb's only adornment.

On a bitterly cold January night in 1888, the telescope saw "first light."

The lens had been carried from its place in the observatory safe and

installed in the telescope on December 31, but stormy weather prevented

observing until, on January 3, a break in the clouds provided the first

chance to put nearly fifteen years of planning and hard work to the test.

One can only imagine the shock and distress that the small party in the

dome must have felt when they found they could not focus the

telescope—and their relief when it was discovered that an error in the

estimate of the focal length had caused the tube to be built too long. A

hacksaw was sent for and the tube unceremoniously shortened. The

image of a "blazing red sun"—the bright star Aldebaran—came into

focus.

Lick's reinterment in the pier of the 36-inch Refractor, 1887.

Lick's funeral, ten years earlier, had been as grand as that for any head

of state. Flags in San Francisco flew at half staff for three days, while

thousands came to view his body. Hundreds followed the hearse,

drawn by four black horses, through the streets of the city to his resting

place in the Masonic cemetery. But early in January 1887, in

accordance with his wishes and at the appropriate stage in the

construction, James Lick was brought, for the first time, to the summit

of Mt. Hamilton, and laid to rest, for the last time, at the base of the

pier, hidden from sight beneath the floor of his great telescope. A

simple plaque inscribed with the words "Here Lies the Body of James

Lick" is the tomb's only adornment.

On a bitterly cold January night in 1888, the telescope saw "first light."

The lens had been carried from its place in the observatory safe and

installed in the telescope on December 31, but stormy weather prevented

observing until, on January 3, a break in the clouds provided the first

chance to put nearly fifteen years of planning and hard work to the test.

One can only imagine the shock and distress that the small party in the

dome must have felt when they found they could not focus the

telescope—and their relief when it was discovered that an error in the

estimate of the focal length had caused the tube to be built too long. A

hacksaw was sent for and the tube unceremoniously shortened. The

image of a "blazing red sun"—the bright star Aldebaran—came into

focus.

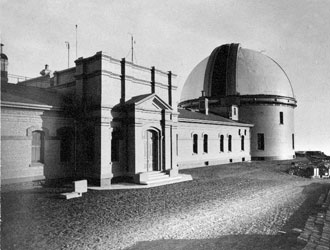

The "Main Building" soon after completion.

The "Main Building" soon after completion.

The Great 36-inch Refractor.

Again clouds and snow descended on the mountain, and another four

days passed before the dome could be opened again. A buildup of ice

prevented the dome from rotating, but with patience born of a decade of

slow progress, Floyd and his men waited for the earth's rotation to

bring a planet in sight of the telescope:

The Great 36-inch Refractor.

Again clouds and snow descended on the mountain, and another four

days passed before the dome could be opened again. A buildup of ice

prevented the dome from rotating, but with patience born of a decade of

slow progress, Floyd and his men waited for the earth's rotation to

bring a planet in sight of the telescope:

"In jittery handwriting, caused by the cold working on his ungloved

fingers, Floyd wrote "We are all waiting in this office (next the big

Dome) for Saturn to come by our shutter, which will be in about 2

hours." When Saturn arrived at about midnight, the group gave up the

relative warmth of the office for the frigid dome interior. The sight of

the ringed planet rewarded them for their patience. 'The definition was

exquisite,' Floyd wrote, '[Saturn] has the silvery brightness of the

moon. All hands were delighted .... There is no doubt that we have the

most powerful optical instrument in the world.'"

from Eye on the Sky, Osterbrock, Gustafson, and Unruh).

Sadly, Floyd's triumph was diluted by illness and disappointment. Chronic heart disease, and bitterness over unfounded criticism of Floyd and the telescope in the San Francisco press, were taking their toll. In February 1888 he wrote to Simon Newcomb: "I am tired and heartily disgusted with the contemptible worries wholly unexpected that beset the closing of my work here. And shall be sincerely glad when the Regents relieve me of responsibility." In April he declared the observatory ready for transfer to the University of California. Less than three years later, Floyd died at age 47.

Text is copyright 1998, Anthony Misch and Remington Stone. Images are copyright University of California and The Mary Lea Shane Archive. The authors are indebted, in particular, to two sources for the material in this essay: Eye on the Sky by Donald Osterbrock, John Gustafson, and W. Shiloh Unruh, University of California Press, 1988, and The Generous Miser by Rosemary Lick, Ward Ritchey Press, 1967.