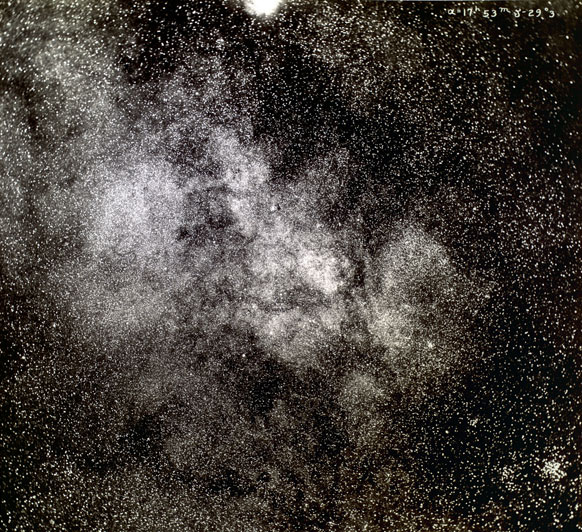

Star clouds in Sagittarius.

By the time of Lick Observatory's founding, a few astronomers had begun to experiment with photography

to record their observations, but visual observing was still the rule. Indeed, Lick's

Great 36-inch Refractor, completed in 1888 and then the world's most powerful telescope,

was originally designed for visual work.

Photography dates from about 1825, but the insensitive emulsions and cumbersone processes of early

photography made it impractical for astronomy. Fifty years of refinement

were required before it took root at the telescope, but in the end its takeover was

rapid and complete. By the early twentieth century,

the photographic plate had put an end to most visual observing by professional astronomers,

and would dominate the field for decades. The human eye—the astronomer's

only detector for all of history—had been replaced by silver crystals

suspended in gelatin on a sheet of glass

(learn more about

the photographic process).

Photographic plates offered two overwhelming advantages.

First, they could accumulate light over long exposures, at last freeing astronomers

of the limit imposed by the eye's rapid refresh rate. Beautfully detailed images of objects

far too faint for the eye to detect could build up in the photo-sensitive emulsion.

By making much fainter objects "visible," photography effectively expanded the observable

universe manyfold. Second, photographic observations left permanent records, free

of observer bias, for later study.

Star clouds in Sagittarius.

By the time of Lick Observatory's founding, a few astronomers had begun to experiment with photography

to record their observations, but visual observing was still the rule. Indeed, Lick's

Great 36-inch Refractor, completed in 1888 and then the world's most powerful telescope,

was originally designed for visual work.

Photography dates from about 1825, but the insensitive emulsions and cumbersone processes of early

photography made it impractical for astronomy. Fifty years of refinement

were required before it took root at the telescope, but in the end its takeover was

rapid and complete. By the early twentieth century,

the photographic plate had put an end to most visual observing by professional astronomers,

and would dominate the field for decades. The human eye—the astronomer's

only detector for all of history—had been replaced by silver crystals

suspended in gelatin on a sheet of glass

(learn more about

the photographic process).

Photographic plates offered two overwhelming advantages.

First, they could accumulate light over long exposures, at last freeing astronomers

of the limit imposed by the eye's rapid refresh rate. Beautfully detailed images of objects

far too faint for the eye to detect could build up in the photo-sensitive emulsion.

By making much fainter objects "visible," photography effectively expanded the observable

universe manyfold. Second, photographic observations left permanent records, free

of observer bias, for later study.

Click on the thumbnails below for more on early astrophotography at Lick Observatory.

Moon, 1893

Moon, 1893

Plate holders

Plate holders

Early plates

Early plates

Pleiades, 1898

Pleiades, 1898

Measuring machine

Measuring machine